History is full of concepts and products that flopped or ended up as nice products used for very limited purposes. But out of all failed or marginalized products, there are some that reappear years or even decades later to become hugely successful. Have you ever stopped to think about why this is?

What makes a flop a success?

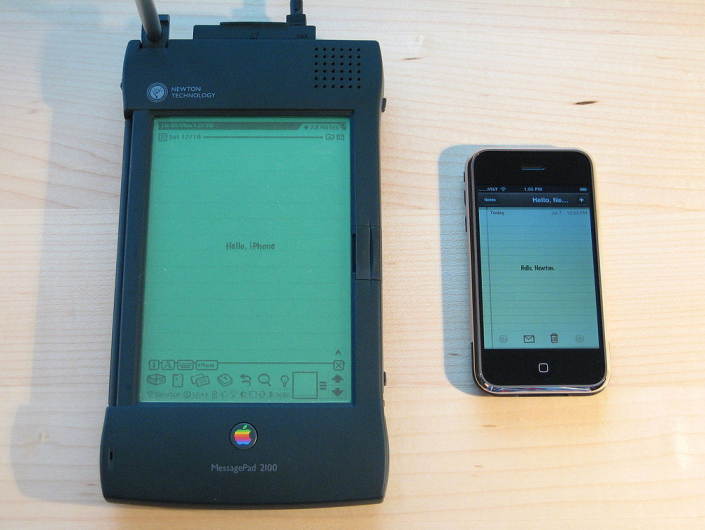

A good example from consumer IT is the Apple Newton (a “personal digital assistant” sold 1993-1998) and the iPhone. The similarities are many, in the hardware, software, ability to install “apps” and so on. Today, knowing how the iPhone is perhaps the single most successful consumer IT device of all time, I have to wonder why the Newton did not do better in its day. Sure, in those days PDAs and mobile phones were two separate devices, but why did the Newton fail when other devices – such as the PalmPilot – did rather well?  Above: The Apple Newton MessagePad 2100, running Newton OS, alongside an iPhone running iOS. Image source: Wikipedia.

Above: The Apple Newton MessagePad 2100, running Newton OS, alongside an iPhone running iOS. Image source: Wikipedia.

After some soul searching, I think I have found the answer—the Newton lacked the ability to accommodate the variations in how different people use it. The Newton concept was great. It had promising usability innovations like real handwriting recognition. It had third party apps. It behaved great in demos. But… it failed to accommodate the variations in peoples’ handwriting. So for most users, the key innovation that was going to make the Newton better than the PalmPilot (who used Graffiti, its own computer-friendly handwriting recognition system) just didn’t work for most users. The innovation became the failure.

The flop of role-based user experiences

Taking an example a bit closer to home, I would argue that the first generation of role-based user experiences (or portals as they were often called then) that appeared around the turn of the millennium were a flop. Not a total flop, but something that became marginalized and used in a narrow set of business processes—in self-service HR, for line managers, and a few other areas. There was pretty much a zero uptake of role-based user experiences in manufacturing, project management, and many other areas.

I argue that the reason we haven’t seen any noticeable number of successful implementations of role-based user experiences in those areas is that there are variations between how businesses work and how they define their roles. To take a simple example – in one organization a project manager may be responsible for staff budget, but in another the staff is given it and the project manager only manages direct costs. In one industry projects are typically a few months long, and in other industries, they last several years. The first generation of role-based user experiences did not make allowance for those variations in a good way. Adapting a first generation role-based interface to the specific needs of an organization and how it defines the roles (and thereby the needs of the role) typically involved:

- Development (programming) of a web part, portlet or whatever the elements of the role-based interface were called.

- To do this, get hold of specific developer skills, or if you don’t have them order a “customization” from your supplier.

- Test what has been developed extensively.

- Plan a maintenance window to deliver and install the new or updated thing.

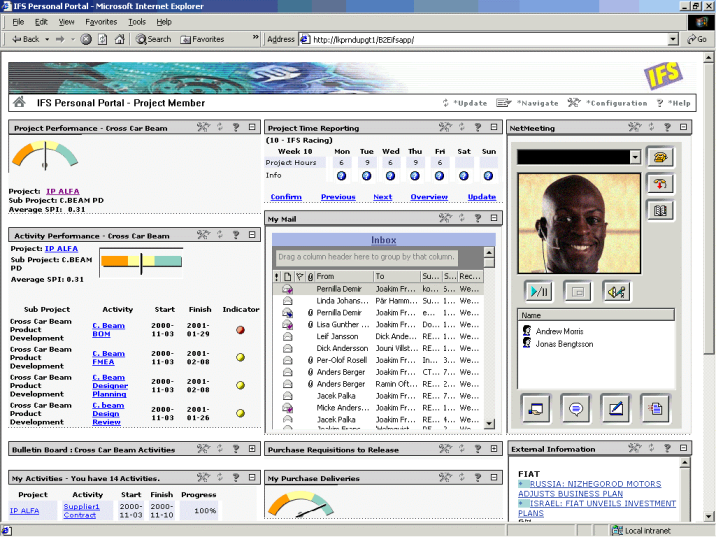

Above: IFS’s first foray into a role-based user experience – the IFS Personal Portal. Beyond setting some configuration parameter values, adapting or developing new content involved programming in Java. The screenshot is from 2001.

Above: IFS’s first foray into a role-based user experience – the IFS Personal Portal. Beyond setting some configuration parameter values, adapting or developing new content involved programming in Java. The screenshot is from 2001.

Few organizations have had the energy, time, money and drive to go through this process repeatedly in order to build and maintain something that fits close to their variation on how they run their business. As a consequence, the role-based interface only presented some, but not all, relevant information. And worse, it presented what appeared to be relevant information but selected or measured in the wrong way. The thing with role-based interfaces is that they can really help to simplify things if they fit exactly the needs of the users. If they don’t they risk causing more confusion or even encourage the wrong behavior. Consequently, although these interfaces seemed rather useful at first glance, few actually saw much usage in real life. The ones that did were those for business processes and roles, such as line management, that are more standardized and similar between organizations.

Indications of breakthrough success

Only in the last year or so have we started to see a new generation of role-based interfaces that handle things better. But still there is variation. Not all attempts meet the four criteria we set up to make sure that IFS Lobby, our newest generation role-based interface, would end up being used and loved, rather than demonstrated and forgotten:

- Adding and adapting content should not require developer skills nor developer tools—it should be possible for a business person to do.

- Design should be true what-you-see-is-what-you-get.

- Changes should be immediately visible, without the need to deliver or install anything, without the need to restart anything.

- People should define the content they want, and the flow/order of things, but not the layout on the page. This way we can automatically and instantly show the content on a range of devices of all sizes.

We really think we have got things spot on now, and I have heard endless stories from our sales and presales teams on just how well IFS Lobby is being received by customers. But the proof, as they say, is in the pudding—in real world usage, not just in making a good impression during demos.

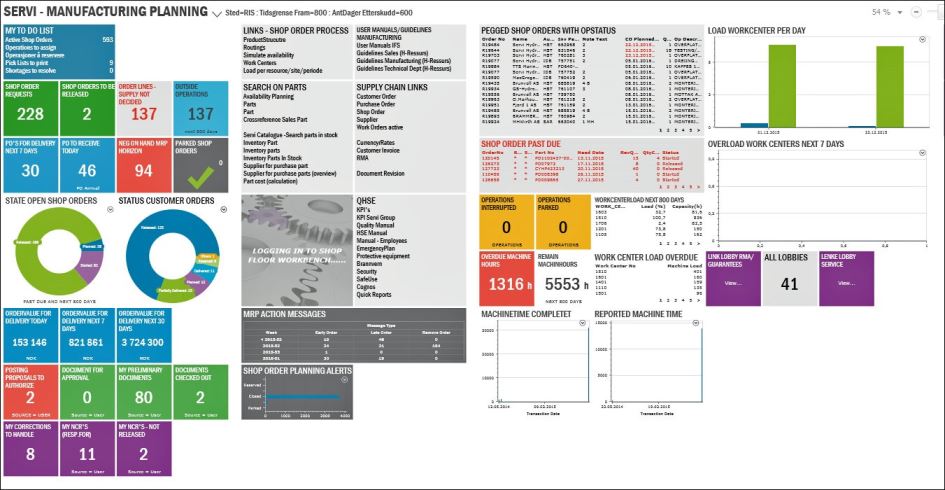

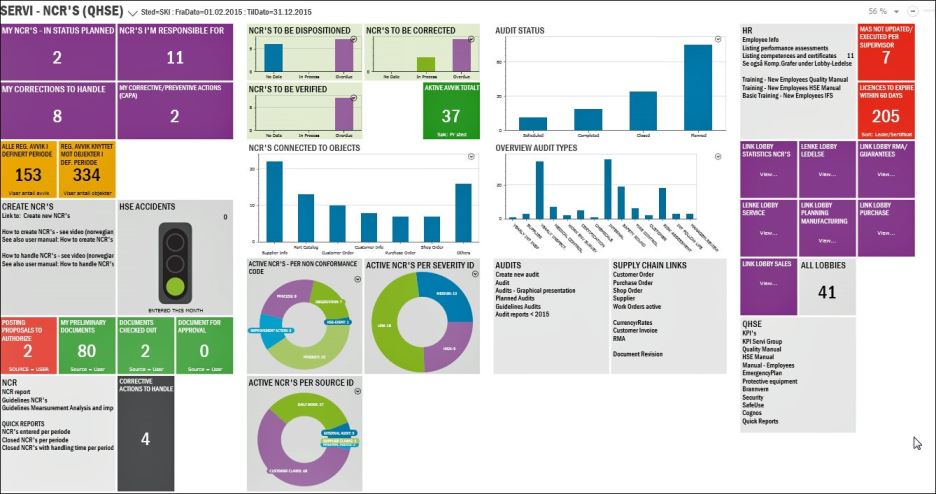

With this in mind, I was very keen to listen to our customer Servi presenting how they were using IFS Lobby at the recent annual conference organized by the IFS user group in Scandinavia. Since Servi went live with IFS Applications in early 2015 they have really got to grips with IFS Lobby. They have created a number of new lobby pages, adapted content of several of the ones that came out-of-the-box with IFS Applications. And most important of all—it was their own super users that did it. No developers!  Above: At IFS’s Scandinavian user group’s annual conference, Anne Lise Halvorsen from Servi demonstrates an IFS Lobby page she created for their end users.

Above: At IFS’s Scandinavian user group’s annual conference, Anne Lise Halvorsen from Servi demonstrates an IFS Lobby page she created for their end users.

Above: Two other lobbies for manufacturing planning and compliance/auditing adapted by Servi themselves to fit their specific needs and roles.

Above: Two other lobbies for manufacturing planning and compliance/auditing adapted by Servi themselves to fit their specific needs and roles.

It is still somewhat early to pass final judgment, but so far all the evidence points to the fact that IFS Lobby is possibly the first implementation of role-based UX that will be universally successful and improve things for every single user of IFS Applications 9.